By Akintunde E. Akinade

Precious in the sight of the Lord is the death of a faithful servant.

Psalm 116:15

Life is a journey; death is a return to earth. The universe is an inn; the passing years are like dust.

Huston Smith

When death finds you, may it find you alive.

An African Proverb

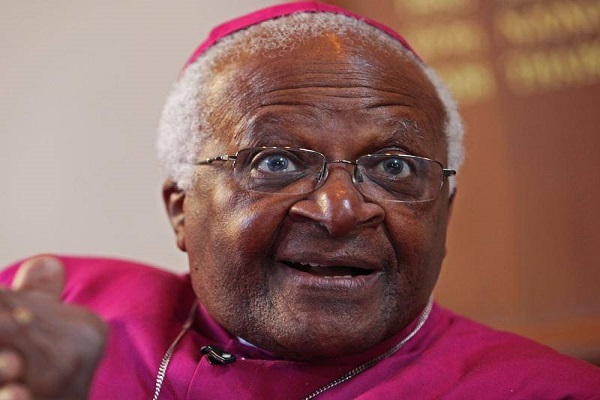

The last email conversation I had with ‘The Arch’ was his prompt acknowledgement of the tribute I wrote for Professor John Samuel Pobee. The two of them served at the Fund for Theological Education in Geneva. In his message, Archbishop Tutu was predictably gracious, generous, and grateful. The world will miss his robust passion for justice, peace, freedom, and human wholeness. In a world awash with pernicious paradigms and petty projects, it is heartwarming to encounter someone who not only spoke truth to power but tenaciously wrestled with issues of mighty significance. He preached against the tyranny of apartheid, advocated for debt relief for poor African nations, grappled with interreligious harmony, gallantly embraced the struggle for a clean environment, rejected wanton and cruel Xenophobia, spoke against the dehumanization of gays, discussed the deep theological implications of forgiveness, and embraced the significance of hope in a world that is sated with so much toxic and centrifugal forces. As a man without cant, his voice was a lighthouse beacon in a tempestuous and stormy sea. As an intrepid sentinel, he consistently kept vigil on the globe until death surreptitiously slipped in on a Sunday, a day of rest. His entire life and ministry were undergirded by an unequivocal hope. This was not just about a futuristic eschatological hope; rather, it was a hope that is wrought in the here and now. His salubrious sense of hope was firmly grounded on his Christian faith and also on the African ethos of Ubuntu. His theological hermeneutics displayed a profound synthesis of both orthodoxy – right belief and orthopraxis – right action. The integrity of his theological vocation was affirmed on the pulpit and on the street. He was at home in the mighty Cathedrals of the world and also while visiting Mumia Abu-Jamal in prison. He was at ease both at Harvard and in Harlem. His prophetic gaze was revolutionary and radical. No doubt, his boundary-breaking projects gave voice to the voiceless.

According to Archbishop Desmond Tutu, in one’s true essence, “you are made for perfection, but you are not yet perfect. You are a masterpiece in the making.” The alchemy of human transformation is wrought through dedication and discernment. No doubt, the rhythm of ultimate transformation energizes and captivates seeking souls. The trappings of the transcendence unveil modalities for experiencing reality in all its various complexities and wonders. One of my former teachers in graduate school, Frederick Streng actually defined religion “as a means of human transformation.” The quest for transformation is very inviting and seductive indeed.

Archbishop Tutu boldly affirmed that: “My humanity is bound up in yours, for we can only be human together.” This observation is a telling affirmation of the bond of Ubuntu that binds all humanity. Ubuntu is an African word that has a universal ramification. It is a Zulu word that captures the spirit and ethos of the philosophical foundation of African societies as a collective whole. It exemplifies a unifying ethos enshrined in the Zulu dictum umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu, that is, “a person is a person through other persons.” This African aphorism posits that we are all contingent beings. This notion challenges the enlightenment philosophical paradigm that celebrated whiteness as the universal standard for humanity. The African model of Ubuntu celebrates humanness and connectedness. John Mbiti interpreted this communitarian vision in terms of “I am because we are, and since we are, therefore I am.” The Venda people of South Africa say that “muthu u bebelwa munwe – A person is born for the other.” Rahman Baba, the popular Pashtun poet remarked: “Humanity is all one body; to torture another is simply to wound yourself.” Ubuntu engenders the cultural sensibilities and stirrings to see the world in a different form. It’s methodology is founded on the firm conviction that human beings need one another in order to be fully human. This goes beyond mere communitarian ethos. Rather, it is based on the fact that human means must indeed be consistent with human ends. The ethos and energy of Ubuntu creates the formidable solidarity among black people from Lagos to Louisiana. The COVID-19 pandemic that has ravaged the entire global landscape since 2020 provides a unique opportunity of evaluating and harnessing our common humanity.

I am in awe of Archbishop Tutu’s incredible capacity to embrace the other. He proclaimed that there is no future without forgiveness. His short piece on forgiveness, “An Invitation to Forgive” is powerful, passionate, and persuasive. I use the article in my class on “Religion, Peace, and Violence” at Georgetown University in Qatar. Every time we use it in class, my students and I come up with new ways of interpreting the abiding affinities between forgiveness and peace. The words of Archbishop Tutu energizes the weary soul: “We each have the capacity to write a new story, and to experience the healing and freedom that comes when we let go of our grievances – when we forgive.” What a significant admonition from a beautiful mind! Truly, this pragmatic exhortation and words of wisdom offer a glimmer of hope for our troubled and sin-sick oikos. It is the veritable balm in Gilead for the despondent soul and spirit.

Sleep well and rest easy, Archbishop Tutu.

We shall miss your stupendous candor, compassion, and courage.

May the ancestors welcome you with glee and gusto.

Good night, humble servant of God.

You ran your race with great grace and goodness, our beloved ‘Arch.’

Rest in peace and power!

* Akintunde E. Akinade is a Professor of Theology at Georgetown University in Qatar. He earned his M.Phil. and a Ph.D. in Ecumenical Theology from Union Theological Seminary in New York City where he studied with both James H. Cone and Kosuke Koyama. He serves on the Editorial Board of The Muslim World, Religions/Adyan, Trinity Journal of Church and Theology, Journal of Interreligious Dialogue, and The Living Pulpit. Within the American Academy of Religion, he has served on the Committee on the Status of Racial and Ethnic Minorities in the Profession, the International Connections Committee, and on the Editorial Board of its flagship journal, the Journal of the American Academy of Religion (JAAR).